by Kyle Bradford.

Winter is here and ants have burrowed deep underground or have sealed themselves off in whatever medium they nest in. Some have filled themselves with glycerol (a kind of antifreeze) and fat reserves to feed on. In any case they are hibernating; giving ant collectors time to reflect on observations from the field season.

This year was a fruitful one for our ant work. We added four species to our County List. For the first time in over two field seasons, we witnessed slave raids on multiple occasions. We even had a friend in the County contact us about seeing this phenomenon. Our firsthand observations resulted in a compilation of photos and gave inspiration to dive deeper into this amazing ant behavior.

Some background on slave-making.

What is curious about slave-making ants is that they have evolved only in the temperate regions of the world. Only 50 ant species out of the 12,500 described are known to have this lifestyle (see reference 2). In the Field Guide to New England Ants, Aaron Ellison and colleagues include ten slave-making species, which are currently known from the region (3). The remaining 40 species occur in the rest of temperate North America, Europe and Asia. Out of the ten known from New England we have found five of these to reside in Columbia County.

Table 1: Slave-making species recorded for New England and Columbia County, NY.

| Species Recorded in New England | Recorded in Columbia County, NY? |

| Formica aserva | Y |

| Formica creightoni | N |

| Formica pergandei | N |

| Formica rubicunda | Y |

| Formica subintegra | Y |

| Harpagoxenus canadensis | N |

| Polyergus cf longicornis | N |

| Polyergus lucidus | Y |

| Polyergus montivagus | N |

| Protomognathus americanus | Y |

Although we say “slaves,” ant slaves are not really analogous to slaves in human society. Instead ants “enslave” different species from their own. Additionally, the slaves in the ant colony are not forced to do anything novel – they just carry on the same tasks as they would have in their own colony. This is more akin to humans domesticating animals for work.

Slave-makers are considered parasites. A parasite is an organism that is dependent on a host for at least part of their life cycle. Slave-maker queens depend on a host to start a colony. In an ant colony all of the workers you see are sterile females. However, there is one queen or in some species multiple queens in the nest who are laying eggs. These eggs metamorphose from larvae to pupae and then into a sterile female, a winged queen, or a winged male. Winged queens and males are only produced for reproduction, whereas sterile females do the work around the nest. At some point in the year, often late summer, the nest will have a reproductive flight referred to as a nuptial flight. All of the winged queens and males will exit the nest to mate. The mated queens then shed their wings and attempt to find a nest site and lay their first eggs.

The difference for slave-making or parasitic species is instead of finding their own nest site they find a host species’ nest and attempt to take it over. They do this by removing or killing the host queen. The benefit of being a parasite is that the queen already has an established, successful nest to start in with plenty of workers to help raise her first young.

Generally, survival rates of newly-mated queens are extremely low. This is especially true in cold climates where harsh weather really makes survival difficult. A parasitic lifestyle may have higher survival rates. This may be part of the reason why slave-makers have evolved in cold climates and not in the tropics.

For ant parasitism to work, the parasite queen must trick the host workers into thinking she belongs in the nest. Ants distinguish their sisters from other ants by their specific pheromones. Parasitic queens have to smell like the nest. The slave-maker queen may do this in a variety of ways, including covering herself in the guts of a queen or worker she killed.

Eventually, as the new queen’s eggs hatch and older workers die, the host species workers begin to be replaced by the parasitic species. This can become a problem because many parasitic species are dependent on host workers for survival. Some more advanced slave-makers (obligate slave-makers) depend completely on their hosts for nest maintenance, foraging, and brood care (nurturing ant eggs into adult ants). When obligate slave-makers experience a shortage of host workers to do such duties around the nest, the parasite workers go on a slave raid.

Generally, raids are most likely to occur during hot, sunny summer afternoons. The process begins when workers are cued that there’s a need for more slave labor. Slave-maker “scouts” exit the nest and begin their search for a host nest. When a nest is found, scent trails are laid back to the home nest. Slave-raiders are recruited, and the stealing of ant larvae and pupae begins. For most slave-making species, the already-enslaved host never participates in slave raiding. However, host species of the western US slave-maker Formica wheeleri have been known to join in on raids (5).

Slave-makers can travel great distances (by ant standards) for their kidnapping activities and are skilled at finding nests. In one raid we witnessed, they traveled nearly 90 feet to the host nest. The host nest was inconspicuous, being hidden under leaf litter. If I hadn’t followed the raiding party I wouldn’t have known a nest was there.

Some details on the lives of two of our most conspicuous slave-making species

Polyergus lucidus, the Amazon Ant.

This is our most fascinating slave-maker. Commonly known as Amazon Ants, Polyergus lucidus is a magnificent shiny, ruby red and has unique mandibles that resemble the curved blades of sickles. These mandibles are specialized for combat but are impractical for chores around the nest.

The Amazon’s piercing mandibles

The Amazon’s piercing mandibles

This species does not live in the Amazon or any other tropical region. Instead they are endemic to northern North America. Their distribution is from Southern New England west to Wisconsin and south to high elevation meadows in the Carolinas (9). The common name refers to the Amazon warrior women in Greek mythology, this is fitting because all worker ants are females. These ants like to fight and pillage, but otherwise live quite a royal lifestyle. They are incapable of feeding themselves or rearing their young, instead depending on slaves for these tasks.

The above photo shows a winged Amazon queen on the left and the slave species Formica incerta on the right. In any ant colony, the queens are crucial to the success of a species. So when there are winged virgin queens in the nest, workers are likely to protect them. In the photo the slave species is escorting the Amazon queen back to safety after being disturbed. This task wouldn’t be done by an Amazon worker. In fact, when an Amazon nest is disturbed the Amazon workers run around erratically trying to sink their teeth into the intruder. If they can’t find the intruder, they quickly go back underground leaving the slaves to fix the damage.

An Amazon worker on the attack.

An Amazon worker on the attack.

The Amazons seem rare in Columbia County, and are listed by the IUCN as “vulnerable to endangerment.” We have only seen them in two locations: in a Philmont cemetery and a pasture at Hawthorne Valley. The Philmont cemetery colony was found in 2013. When I revisited it in 2014 it was no longer active. Amazons may have relocated their nest. Nest relocations can be quite common for some ant species. However, one distinctive reason among slave-makers is to relocate to gain access to more host colonies after local exploitation (1). In 1910 Wheeler suggested this for Amazons, although some have speculated that there are other reasons for Amazon nest relocation (6, 7).

It is also noted that Amazons are susceptible to local extinction, because they are dependent on large stable populations of host species. If abundant host populations are not stable, because of disturbance, Amazons are not likely to survive in that location (4).

The two sites where we have found Amazons. They tend to like dry open habitats where there is an abundance of their host species Formica incerta.

The two sites where we have found Amazons. They tend to like dry open habitats where there is an abundance of their host species Formica incerta.

Grace Barber, a graduate student at UMass Amherst, has been working on ants in the Albany Pine Bush. She has found Amazons there and has posted a fantastic video of their slave raid!

Formica subintegra

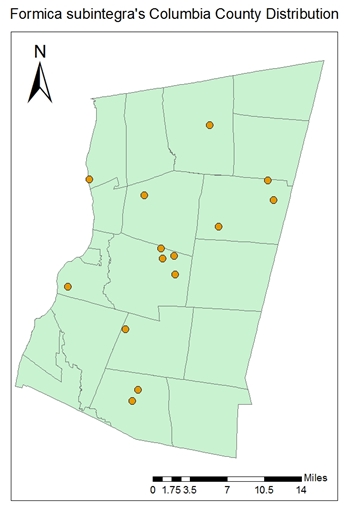

Two of the slave raids we witnessed this year were from the species Formica subintegra. We have found these ants in open forest and meadow habitats.

subintegra is widespread in the County.

subintegra is widespread in the County.

One raid happened on the sun exposed ledges around No Bottom Pond in Austerlitz during an August afternoon. The following photographs are from that raid.

Part of the subintegra raiding party.

Part of the subintegra raiding party.

An unlucky host species becomes defenseless as masses of raiders enter the nest.

An unlucky host species becomes defenseless as masses of raiders enter the nest.

Formica subintegra have special enlarged glands that secrete what EO Wilson has termed “propaganda substances” (8). These chemicals are effective in alarming the host colony. Instead of fending off the raiders they are put into a frightened frenzy out of the nest. This makes it much easier for the slave-makers to enter the nest and take brood. Any resisting hosts that haven’t fled are out-numbered and easily defeated.

Generally, raided host nests by subintegra are not destroyed. I have not seen any description of subintegra killing a queen during a raid, and presumably a raided nest can recover.

A subintegra looks on as two of her sisters drag out a decapitated host as they start raiding the nest.

A subintegra looks on as two of her sisters drag out a decapitated host as they start raiding the nest.

subintegra carrying a stolen pupa back to her home nest.

subintegra carrying a stolen pupa back to her home nest.

It was a pleasure observing these slave raids in the field. These animals that share our landscape are truly unique and fascinating. If you are out on a hot summer day in a dry oak forest or an old field keep an eye on the ground. You might be lucky enough to see a march of Amazons or a raid in the leaf litter.

For Further Reading

A Field Guide to New England Ants – Aaron Ellison – This is what we use for species level identification. It has ecological information for each species and is geared toward the layperson. It does have an overview of basic ant ecology.

Journey to the Ants – Bert Holldobler and EO Wilson – A condensed, non-technical overview of interesting myrmecology (ant studies) especially that of Holldobler and Wilson’s. It is combined with photographs and neat illustrations. Has a chapter on social parasites which includes slave ants.

Adventures among Ants – Mark Moffett – A taste of ant ecology from around the world with spectacular photographs. Also has a chapter on slave-makers with information pertaining to species we have.

Full Works Cited

- Apple, J., Lewandowski, S., & Levine, J. (2014). Nest relocation in the slavemaking ants Formica subintegra and Formica pergandei: A response to host nest availability that increases raiding success. Soc.

- D’Ettorre, P., & Heinze, J. (2001). Sociobiology of slave-making ants. Acta Ethol, (3), 67-82.

- Ellison, A., Gotelli, N., Farnsworth, E., & Alpert, G. (2012). A Field Guide to the Ants of New England. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Fisher, B., & Cover, S. (2007). Ants of North America: A Guide to the Genera. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Holldobler, B., & Wilson, E. (1994). Journey to the Ants: A Story of Scientific Exploration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Kwait E.C. and Topoff H. (1983). Emigration raids by slave-making ants: a rapid-transit system for colony relocation (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Psyche (90), 307–312.

- Marlin A.J.C. (1971). The mating, nesting and ant enemies of Polyergus lucidus Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Am. Midl. Nat. (86), 181–189.

- Regnier, F., & Wilson, E. (1971). Chemical Communication and “Propaganda” in Slave-Maker Ants. Science, 172(3980), 267-269.

- Trager, J. (2013). Global revision of the dulotic ant genus Polyergus (Hymenoptera: Formicidae, Formicinae, Formicini). Zootaxa, (4), 548-548.