Spring wildflowers are the most prominent feature in our forests at this time of the year, while cold-season weeds are most prominent in the vegetable fields. If you want to see images of the spring wildflowers in the forests of Hawthorne Valley, please go into the archive and find the blog we posted on April 30, 2011.

Today, I am going to share the results of a little inventory of early season weeds found during the last two weeks in the vegetable fields at Hawthorne Valley Farm. (Be assured, the farmers have been very busy discouraging the weeds from completely taking over and replacing them with neat rows of vegetable seedlings…)

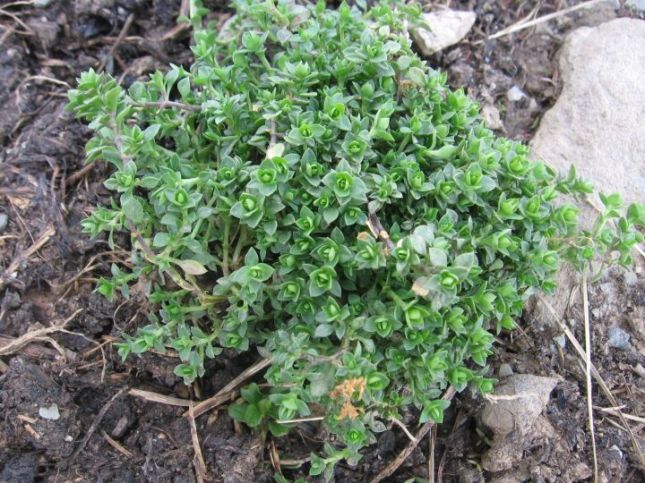

Probably the most common and ubiquitous weed of early spring is Common Chickweed (Stellaria media). It is originally from Europe, but now found on all continents, including Antarctica. It was documented in New England as early as 1672. Common Chickweed is very hardy and often stays green under the snow. Its trailing stems can be several feet long. It grows very quickly and is capable of producing seeds five weeks after germination. No wonder, that certain garden beds are all but covered in it!

Common Chickweed is a member of the Pink Family (Caryophyllaceae) and is characterized by small opposite leaves with a pointed tip. The flowers are composed of five deeply cleft petals.

Tender leaves of Common Chickweed can supposedly be eaten raw as an addition to salads or boiled and served as greens. A tea of this herb is traditionally used to relieve coughs and externally for skin diseases and to allay itching. An infusion of Chickweed is also an ingredient in a skin healing salve prepared here in Columbia County on Red Oak Farm.

A close relative is the introduced Mouse-Eared Chickweed (Cerastium fontanum ssp. vulgare). It too has small opposite leaves, but they are hairy and their tip is more rounded.

There are several other early season weeds in the Pink Family, all recognizable by their opposite leaves. My current assessment is that they are the introduced Bladder Campion (Silene vulgaris = S. cucubalus), White Campion (Silene latifolia = Lychnis alba), and Ragged-Robin (Lychnis flos-cuculi).

The following weed, which I tentatively identified as Bladder Campion (Silene vulgaris), has very regularly-spaced, extremely smooth, opposite leaves.

The weed below, tentatively identified as White Campion (Silene latifolia), has much larger, slightly hairy leaves that emerge closely spaced, almost creating a rosette.

Finally, these very narrow, smooth, and opposite leaves likely belong to Ragged-Robin (Lychnis flos-cuculi).

This sums up the prominent opposite-leaved weeds of early spring.

The next group are the weedy members of the Mustard Family (Brassicaceae), which also happens to include many of our cultivated plants, such as Arugala, Broccoli, Cauliflower, Brussel Sprouts, Kohlrabi, Cabbage, and Kale. Many of these weeds start the season as basal rosettes.

Currently the most prominent in the fields around here is Shepherd’s Purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris). This weed comes from southern Europe and was reported in North America prior to 1672. Its basal rosette is slightly reminiscent of Dandelion, but its leaves are more deeply divided and the leaflets of interesting, irregular shapes (and extremely variable from plant to plant). A broken-off leaf does not exude white milk (as it would in Dandelion or Chicory) and, upon closer inspection (hand lens!), Shepherd’s Purse has branched hairs to help with its identification. Sometimes, these plants can’t wait to flower and instead of growing a proper flowering shoot, they produce a few flowers in the center of the rosette.

Some rosettes have less divided leaves…

… some more. But like many early season weeds, Shepherd’s Purse always has a long taproot.

Below is a typical example of a flowering Shepherd’s Purse. The flowering shoot emerges from the center of the rosette and bears only slightly divided or toothed leaves. The flowers are tiny, white and have four petals, like all members of the Mustard Family.

The young leaves (gathered before the flowers appear) of Shepherd’s Purse can reportedly be used in salads or prepared like spinach. Dried seedpods make a pepperlike seasoning. Traditionally used as a diuretic, to stop bleeding, and during childbirth for its uterine-contracting properties.

Field Penny-Cress (Thlaspi arvense) is another very common early season weed in most vegetable fields at Hawthorne Valley Farm. It originates in the eastern Mediterranean region and was first reported on this continent from Detroit in 1701. As one apprentice observed, it almost looks like Corn Mash. It is considered an edible plant for salads, cooked greens, and seasoning. But it also bears the name “Stinkweed” and supposedly gives meat and milk an unpleasant flavor if animals consume a lot of it.

When Field Penny-Cress is getting ready to flower, its axis begins to elongate, just like in a bolting lettuce and most other rosette forming plants.

An intense peppery taste identifies the following weed as Field Pepperweed (Lepidium campestre). Although it is considered edible, just like its cousins mentioned above, it is a bit strong for my taste. Its leaves are not as deeply divided and as closely hugging the ground as those of Shepherd’s Purse, but they are also not as smooth-margined and organized-looking as those of Field Penny-Cress…

The following weed, which looks like a hairy Dandelion, is actually also a member of the Mustard Family, most likely a Hedgemustard (Sisymbrium officinale).

Continuing with variations on the theme of basal rosette, these smooth and very round-lobed leaves belong to Wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris). This is another species that basically stays green below the snow. The young leaves are supposedly excellent when picked while the nights are still frosty and can be added to salads or cooked like spinach. With warmer weather, the leaves become very bitter, but the tight clusters of flowerbuds can then be boiled and served like broccoli.

Finally, here is a mustard weed that somewhat breaks the basal rosette stereotype. Its young plants are upright and its leaves entire. However, the branched hairs (a character it shares with the otherwise very different-looking Shepherd’s Purse) make me believe we are looking at Wormseed Mustard (Erysimum cheiranthoides).

Change of gears: let’s look at a couple of weeds with roundish, opposite leaves. Their square stems (amongst many other characteristics) place them in the Mint Family. The first one is Ground Ivy (Glechoma hederacea), a very common weed of lawns, pastures, and obviously also fields. It is a creeping plant which roots at the nodes. Its opposite leaves are born on long stalks. Crushed leaves are aromatic, medicinally-smelling. Traditionally, a leaf tea was used for lung and kidney ailments and as “blood purifier”. Externally, it is a folk remedy for cancer, backaches, bruises, and hemorrhoids. Supposedly, the dried leaves make a fine herbal tea when steeped for 5-10 minutes in hot water.

The other weed species is quite similar and also belongs to the Mint Family. But its shoots are more upright, not rooting at the nodes. Its opposite leaves are stalked in the lower parts of the plant but in the upper part they are sessile, attached directly to the main shoot. This identifies it as the much less common (in our region) Henbit (Lamium amplexicaulum).

Ground Ivy flowers are bluish-purple, while Henbit flowers are pink.

Another pretty early flower is produced by Bird-Eye Speedwell (Veronica persica), a member of the closely Snapdragon Family (Scrophulariaceae). Its toothed leaves are opposite along the base of the shoot, but near the flowers they become alternate.

The sky blue flowers with their prominent dark blue “landing strips” that guide bees to the nectar, are presented on relatively long stalks.

The Corn Speedwell (Veronica arvensis) looks very similar, but tends to have smaller leaves and its tiny blue flowers have no or only very short stalks.

We will close with a few “oddballs”. Here are the three-foliate, Strawberry-like leaves of Rough Cinquefoil (Potentilla norvegica), a member of the Rose Family (Rosaceae) that will soon be producing little yellow flowers. Rough Cinquefoil is considered native to this continent and one of the few native plants that readily associate with cultivated soil.

Somewhat similar in appearance are the palmate (“hand-like”) leaves of a member in the Geranium Family, possibly Carolina Geranium (Geranium carolinianum).

Finally, there is a little violet, aptly named Field Violet (Viola arvensis) that can become very prevalent in some vegetable fields. It has toothed, long-stalked leaves of variable shape …

and flowers very early in the season.

The information about the date when an introduced weed species was first documented on this continent was gleaned from “Weeds of Canada and the Northern United States” by France Royer & Richard Dickinson. I consulted the Peterson Field Guides on “Edible Wild Plants” by Lee Allen Peterson and “Eastern/Central Medicinal Plants” by Steven Foster and James Duke about culinary and medicinal uses of the weeds. Weed identification was facilitated by “Weeds of the Northeast” by Richard H. Uva, Joseph C. Neal and Joseph M. DiTomaso, and the “Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada” by Gleason & Cronquist.

As I indicated in the text, some of the identifications are tentative, because they are based on sterile specimens. Please do let me know if you detect any obvious errors in my best guesses. Thanks!