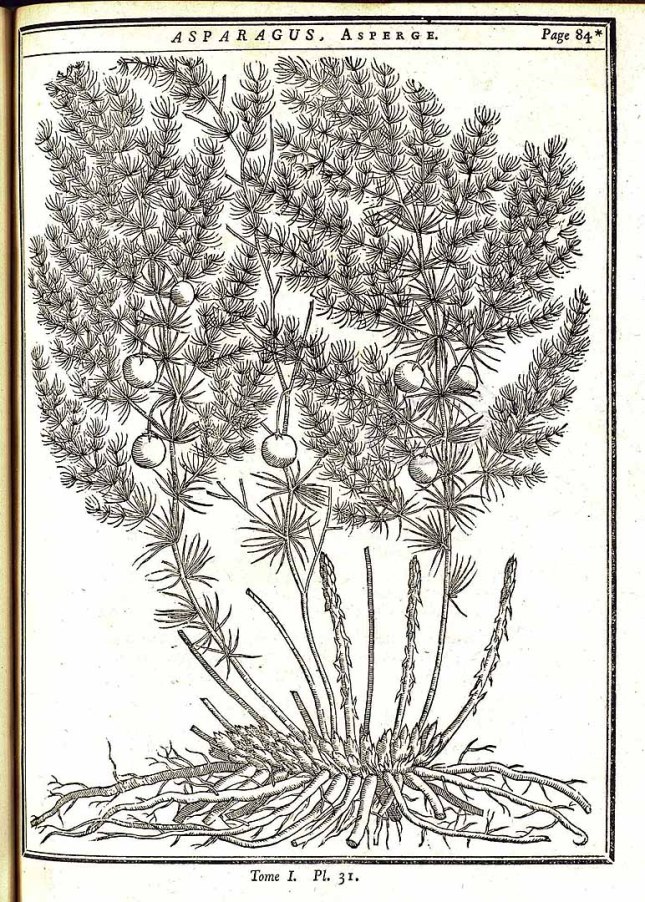

An early illustration of Asparagus from Duhamel du Monceau’s Traité des arbres et arbustes, vol. 1: t. 31 (1755); image from http://www.plantillustrations.org. Asparagus was among the earliest European vegetables to be brought to the New World.

As a child, the wispy, ferny fronds of wild Asparagus were always rather magical to me. It was as if the staid crop had let its hair down as it roamed the ditches and roadsides. It should not be surprising that Asparagus is widely feral; it has been here for a while. Asparagus has been recognized as a vegetable for millennia and apparently was planted in some of the first new world vegetable gardens, possibly because of its early-season arrival to the table, its hardiness and perennial habit, and its purported medicinal properties. In addition, its original native Western Europe seaside habitat may have preadapted it to road salt.

Asparagus was listed among the vegetables in William Penn’s colony in 1685. By 1747, Peter Kalm found it growing wild in various places, including along the Hudson north of Albany. Jefferson included abundant observations on its planting in his garden notebooks starting in 1767, and it was being sold commercially in New England in the same century. It was widely naturalized in NY by the early 1800s, and, by the mid 1800s, it was being grown extensively, including in 10-20 acre fields on Long Island for sale in NYC.

A late 19th or early 20th century Massachusetts asparagus farm, from Hexamer’s Asparagus : its Culture for Home Use and for Market : a Practical Treatise on the Planting, Cultivation, Harvesting, Marketing, and Preserving of Asparagus. Large asparagus farms served major East Coast cities.

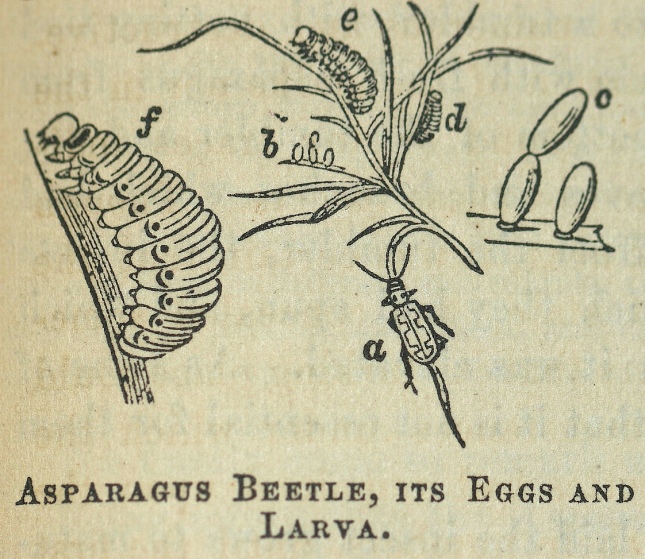

As is often the case with newly introduced plants, for many years Asparagus apparently had few enemies. However, in 1862 New York State Entomologist Asa Fitch began his annual report with this line, “Much the most important entomological event in our State the present year has been the appearance upon the asparagus on Long Island of an insect new to us in this country, and doing great injury to this important crop, threatening even its total destruction.” The Common Asparagus Beetle had arrived.

The illustration that accompanied Asa Fitch’s 1862 description of the Common Asparagus Beetle upon its first recorded arrival to North America, from the 8th Report on the Noxious and Other Insects of the State of New York. Damage was apparently quick and extensive.

The Common Asparagus Beetle in action, as illustrated in Hexamer’s work. The beetles seem to attack the stalk and head while the grubs appear to spend more time eating the leafy fronds.

A sickly, beetle-damaged Asparagus stalk. Adults and grub feed directly on the plant, and extensive egg-insertion may stunt stalk growth.

The Common Asparagus Beetle.

On heavily occupied plants, the activity can be crowded.

Mating Common Asparagus Beetles on Asparagus. The wet-looking scrapes on the Asparagus stalks are from its feeding.

After some research, Fitch concluded that the Common Asparagus Beetle (Crioceris asparagi) had probably landed on these shores some time in 1857 or 1858. He could offer little by way of control except, after dismissing the use of skunks (who did seem to enjoy beetle fare but were “in such bad odor”), the use of free-ranging fowl. For the next two years, growers apparently despaired but then a “small, shining black parasitic fly” appeared as a “deliverer” and the destruction abated somewhat. The mysterious parasite apparently then disappeared, and the beetle continued to spread, probably reaching our area (Columbia County, NY) around the turn of the century. In 1909 (see this paper), the parasite was finally captured and identified as the small wasp Tetrastichus aparagi. Subsequently, and not surprisingly in retrospect, this wasp was found to be identical to T. coeruleus, a wasp known to parasitize the Common Asparagus Beetle in its native Old World homeland.

A probable Tetrastichus coeruleus, the wasp that saved the Asparagus crop.

The wasp has not disappeared again, and it is apparently crucial to controlling Common Asparagus Beetles. Estimates are that it kills approximately three quarters of the eggs produced by this beetle. Interestingly, American economic entomologists, struggling with the late 19th century rampages of the Asparagus Beetle, seemed somewhat baffled that Europeans could not provide them with any adequate control measures. It now seems likely that, with this little wasp already ‘on the job’, Europeans rarely needed extra measures.

Before describing some of what is known of the life cycles of both wasp and beetle, it’s important to emphasize the fact that Asparagus is a perennial; it may produce a crop for a decade or more. Unlike the case with annual crops, asparagus fields are not being ploughed under and moved every year, and so populations of both pest and parasite can build up over several years.

Asparagus is a perennial crop that may be harvested for up to a dozen years. This allows predator/pest communities to develop over time.

The Common Asparagus Beetle overwinters in the soil as an adult. These beetles then emerge in the Spring and begin to feed on the rapidly growing asparagus shoots. Soon, rows of their tiny, neat eggs begin to appear on asparagus stalks, (The only analogy I can think of for the appearance of the eggs is that of a school of shark fins cutting through an asparagus ocean… OK, that probably doesn’t help.) After a week or so, these hatch into black-headed, grey-bodied grubs who feed avidly for a couple of weeks then pupate in the soil for a dozen days or so, re-emerging as the second generation a bit more than a month after their parents. These beetles go on to produce another generation, and, it is those beetles or their progeny who then overwinter.

A Common Asparagus Beetle grub together with eggs of the same species.

Several Common Asparagus Beetle grubs on a young Asparagus frond that they have nearly stripped of its outside layer.

A Common Asparagus Beetle among eggs of the same species. I’m guessing the yellowish egg is recently laid, but I may be wrong.

Although egg laying on Asparagus should be the norm, this beetle decided to try grass. Since young larvae appear to travel in search of the appropriate Asparagus plant for feeding, perhaps these future hatchlings will make it to a nearby Asparagus stalk.

Common Asparagus Beetles reportedly overwinter as adults in litter, under tree bark, and in the somewhat hollow stems of cut Asparagus such as shown here.

While the adults scar the surface of the large stalks and eat the ‘scales’ of the heads, the grubs seem to favor the finer vegetation of the branching asparagus ‘ferns’, and can quickly girdle and strip smaller plants. The action of the adults, while apparently not as immediately dramatic, can scar and stunt the asparagus shoots growth, sometimes causing the stalk to do a complete loop the loop and rendering them unfit for sale.

Meanwhile, the wasp has been passing winter in the pupae of the eggs it parasitized the previous year. It soon emerges and begins its work. One of the characteristics that apparently makes this wasp so effective in control is that it is not only a parasite, it is also a predator. The adult wasp both consumes and lays its eggs in (that is, ‘oviposits’) the beetle’s eggs.

A sequence of shots showing the parasitic wasp approaching and sensing an egg, inserting its ovipositor in two different locations on the same egg, and apparently eating or at least tasting some of the content. The glistening circles evident on a couple of eggs are the insertion points. The ovipositor comes out of the central ventral portion of the abdomen, not the tip and is visible in a couple of the pictures.

- The somewhat deflated eggs visible in this shot may be the work of a hungry wasp, although I still need to insure that I can tell hatched from consumed eggs.

The wasp’s general behavioral sequence, based on the aforementioned early 20th century observations and a more recent European paper, is that a wasp approaches an egg and ‘sniffs’ or drums it with its antennae. It then makes the choice to eat, oviposit in, or reject the egg. Younger eggs seem to be favored for eating, while older eggs are favored for oviposition, although, on average, most eggs are rejected outright.

Egg consumption is an interesting behavior. Rather than simply walking up to an egg and taking a bite, the wasp seems to macerate the contents through rhythmical insertions of its ovipositor (see this video of the same wasp pictured here) and then lap up the contents. According to the above mentioned papers, actual oviposition involves a more tranquil insertion maintained for “several minutes”.

One last twist involves what happens next: the parasitized beetle egg hatches and the grub develops normally and pupates in the soil. This was clearly a head scratcher for early observers. But patience finally revealed the end result – the pupae never hatch, at least they don’t produce an adult beetle, instead, up to 10 wasp larvae emerge from the hollowed out beetle pupa. The wasp thus appears to practice delayed development, coordinating its own developmental rush to the pupation stage of the beetle. One possible advantage of this is that the young wasps can overwinter as larvae and/or pupae snug within the small underground cell originally created by the parasitized beetle larvae. The adult wasps then emerge in spring to renew the cycle.

The Spotted Asparagus beetle is commonly found with the Common Asparagus Beetle although, aptly enough, it is usually less common. The beetle in the lower image has decided to hang out on an adjacent weed rather than the Asparagus itself.

- The Spotted Asparagus Beetle usually puts its eggs on the Asparagus flower bud or berry rather than the stalk, so I’m guessing that is who laid these eggs, but I wasn’t present at their arrival.

The Common Asparagus Beetle and the parasitic wasp are not the only visitors to Asparagus. The Spotted Asparagus Beetle (Cioceris duodecimpunctata) arrived somewhat later and has not been as damaging. Its eggs are laid on the Asparagus berries, and its larvae apparently confine their feeding to that part of the plant. While often present, they seem to be generally less abundant than the Common Asparagus Beetle. Another species of wasp is thought to parasitize them. True Bugs sometimes also feed on the eggs, while the maggots of certain flies are known to bore into the Asparagus stems. In addition, passersby regularly alight on the Asparagus stalks, as they would on almost any piece of vegetation. There’s obviously a lot more going on here, but that’s enough for one posting!

Thanks to my colleagues at Hawthorne Valley Farm and the Hudson Valley Farm Hub for tolerating my snooping.

- This wasp, a different species from the one pictured earlier, spent a while excitedly clambering over a grub-laden Asparagus frond but, in the end, it just flew away.

- This fly was moving up and down an egg-spotted Asparagus stem, apparently cleaning up some of the spilled juices.

- So far as I saw, this fly never did anything but perch. Several fungus-filled fly mummies were found nearby. I don’t know the species of fly, but perhaps these were simply using the Asparagus’ high and handy perches.

- This nymph of a True Bug patrolled some egg rows, apparently (although not definitively) sucking out the contents of some of them… think food-filled balloons.

- And, amongst it all, a spider waited patiently; the Asparagus was as good a place as any for some hunting.

-

- This red mite seemed to be sucking on a beetle egg, but perhaps it was only imbibing nearby plant juices.